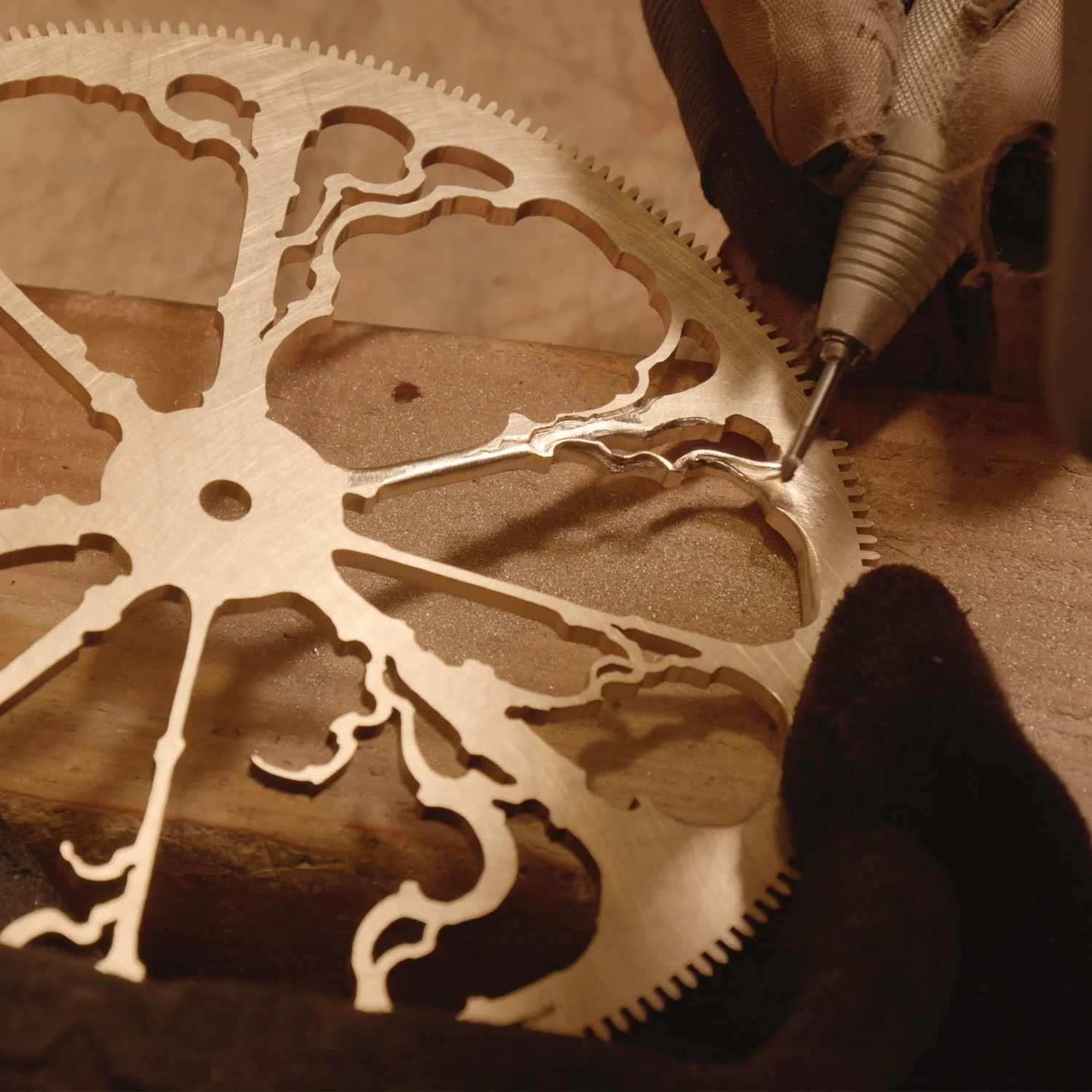

Some steel parts in a clock require very specific heat treating and hardening techniques, followed by many hours of precise polishing. The geometry is often crucial, which calls for a slow and steady approach with a variety of small, very fine grit stones, and polishing with soft sticks and micro-grit (.5 micron) polishing paste.

The first photo and video show what I use to harden steel. It’s a kiln that holds salt at a molten 1500 degrees. When steel is immersed in this salt-bath, the metal is heated very evenly, and precisely. Just 10-15 minutes of immersion brings the part to 1500 degrees. Even better, since it’s immersed, the air can’t get to it, which avoids carbon scaling on the surface.

Immediately after removing the parts from the kiln, they’re quenched in oil. For parts like the clock escapement, the metal is left in this fully hard state. For springs, I have a second, smaller kiln that I use to temper the steel.